When you try to communicate or understand ideas, words do not always do the trick. Sometimes the most effective approach is to make a simple sketch of this concept – for example, a circuit diagrams could help understand how system works.

But what happens if artificial intelligence could help us explore these visualizations? Although these systems are generally competent to create realistic paintings and caricatured drawings, many models fail to capture the essence of sketch: its iterative process, which helps humans, which helps humans to think and modify the way they want to represent their ideas.

A new drawing system of the computer intelligence laboratory and artificial MIT (CSAIL) and the University of Stanford can sketch more like us. Their method, called “sketchage”, uses a multimodal language model – AI systems that train on text and images, such as the Sonnet Claude 3.5 of Anthropic – to transform invites into natural language into sketches in a few seconds. For example, he can scribble a house alone or by collaboration, drawing with a human or incorporating a textual entry to sketch each part separately.

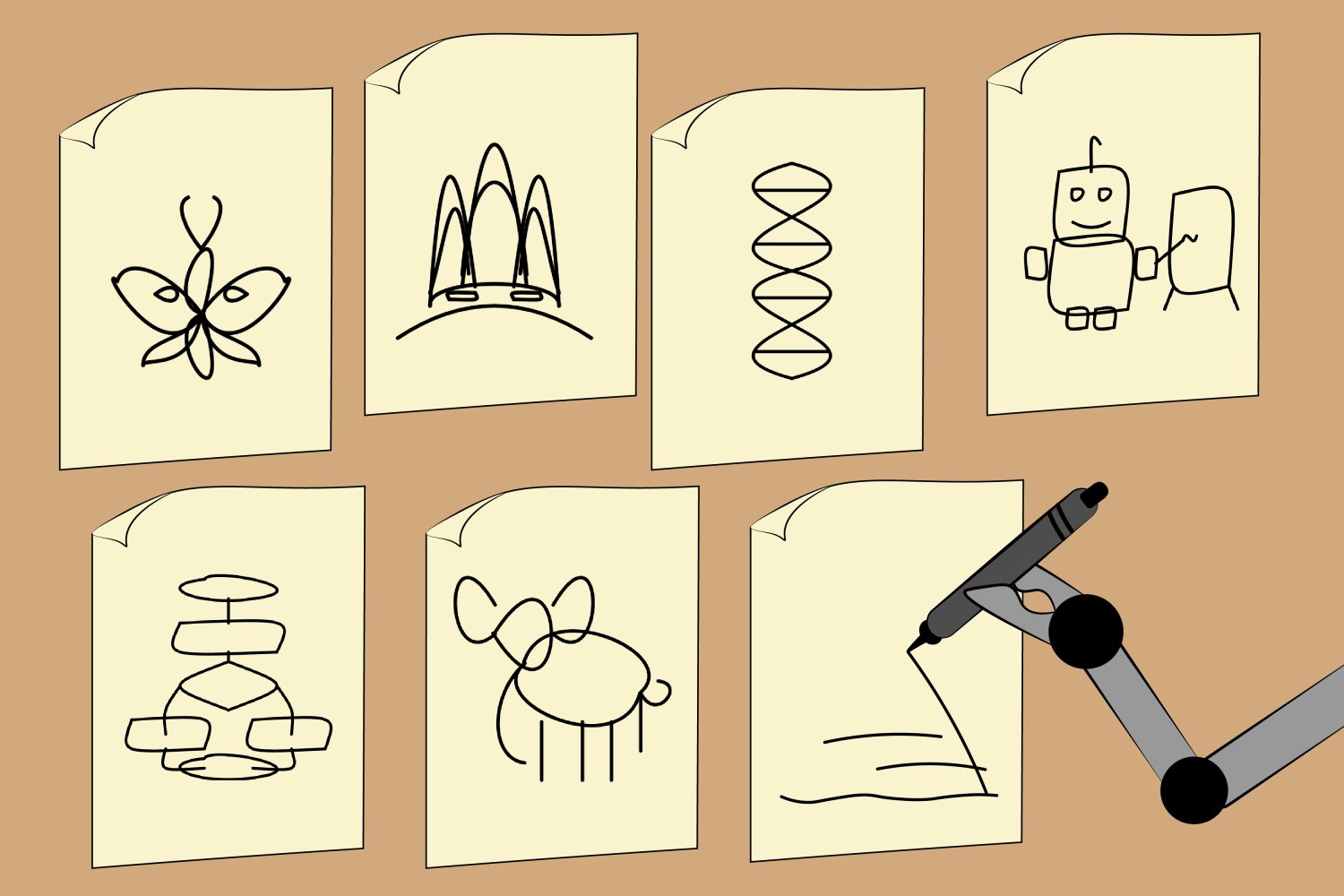

Researchers have shown that sketches can create abstract drawings of various concepts, such as a robot, a butterfly, a DNA propeller, an organization chart and even the Sydney opera. One day, the tool could be extended to an interactive art game that helps teachers and researchers schematize complex concepts or give users a quick drawing lesson.

Csail Postdoc Yael Vinker, who is the main author of a paper Presentation of Sketchage, notes that the system introduces a more natural way for humans to communicate with AI.

“Not everyone is aware of the quantity they attract in their daily life. We can draw our thoughts or workshop ideas with sketches, ”she says. “Our tool aims to imitate this process, which makes multimodal language models more useful to help us visually express ideas.”

Sketchage teaches these models to draw a blow by blow without training on any data – the researchers have rather developed a “sketch language” in which a sketch is translated in a numbered sequence of blows on a grid. The system received an example of how things like a house would be drawn, each stroke labeled according to what it represented – as the seventh blow being a rectangle labeled as a “front door” – to help the model to become widespread in new concepts.

Vinker wrote the newspaper alongside three Csail affiliates – Postdoc Tamar Rott Shaham, undergraduate researcher Alex Zhao and Professor Antonio Torralba – as well as the research researcher at Stanford University, Kristine Zheng, and the assistant professor Judith Ellen Fan. They will present their work during the 2025 conference on computer vision and the recognition of models (CVPR) this month.

IA sketching capacity assessment

While text models like Dall-E 3 can create intriguing drawings, they lack a crucial component of sketch: the spontaneous and creative process where each stroke can have an impact on global design. On the other hand, sketches' drawings are modeled as a sequence of brain vascular accidents, appearing more natural and more fluid, such as human sketches.

Previous work has also imitated this process, but they have formed their models on man -designed data sets, which are often limited in scale and diversity. Sketchage uses pre-formed language models, which are well informed about many concepts, but do not know how to sketch. When the researchers taught the language models this process, Sketchage began to sketch various concepts on which he had not explicitly trained.

However, Vinker and his colleagues wanted to see if Sketchage was actively working with humans on the sketch process, or if he worked independently of his drawing partner. The team has tested its system in collaboration mode, where a human model and a language model works to draw a particular concept in tandem. The deletion of sketchement of sketches revealed that the features of their tool were essential to the final drawing. In a drawing of a sailboat, for example, the suppression of artificial features representing a mast made the global sketch unrecognizable.

In another experience, CSAIL and Stanford researchers connected different models of multimodal sketches to see who could create the most recognizable sketches. Their default skeleton model, Claude 3.5 Sonnet, has generated the most human vector graphics (essentially based on text files that can be converted into high resolution images). He outperformed models like GPT-4O and Claude 3 opus.

“The fact that Claude 3.5 Sonnet has surpassed other models like GPT-4O and Claude 3 Opus suggests that this model processes and generates information related to visuals differently,” explains the co-author Tamar Rott Shaham.

She adds that Sketchage could become a useful interface to collaborate with AI models beyond standard text-based communication. “While the models are progressing in the understanding and generation of other methods, such as sketches, they open new ways for users to express ideas and receive answers that seem more intuitive and human,” explains Shaham. “This could considerably enrich interactions, which makes AI more accessible and versatile.”

Although the sketching prowess of sketches are promising, this cannot yet make professional sketches. It makes simple concepts by using stick figures and scratches, but fights to scribble things like logos, sentences, complex creatures such as unicorns and cows, and specific human figures.

Sometimes their model also misunderstood user's intentions in collaborative drawings, such as when Sketchage attracted a rabbit with two heads. According to Vinker, this may be due to the fact that the model breaks out each task into smaller steps (also called “chain of thought” reasoning). When you work with humans, the model creates a drawing plan, potentially misinterpreting which part of this trigger of a human contributes. Researchers could possibly refine these drawing skills by forming synthetic data from diffusion models.

In addition, Sketchage often requires some incentive cycles to generate human -shaped scratches. In the future, the team aims to facilitate interaction and sketch with multimodal language models, including refining their interface.

However, the tool suggests that AI could draw various concepts such as humans, with human collaboration step by step, which results in more aligned final conceptions.

This work was supported, in part, by the US National Science Foundation, a Hoffman-Yee subsidy of the Stanford Institute for Human Centered IA, the Hyundai Motor Co., the US Army Research Laboratory, the Zuckerman Stem Leadership Program and a Viterbi scholarship.