The research which crosses the traditional limits of academic disciplines and the boundaries between the university world, industry and government is increasingly widespread and has sometimes led to the FRAI of new important disciplines. But Munther Dahleh, professor of electrical engineering and computer science, says that these multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary works often suffer from a number of gaps and disabilities compared to more traditional disciplinary work.

But more and more, he says, the deep challenges we face in the modern world – including climate change, the loss of biodiversity, the way of controlling and regulating artificial intelligence systems, as well as the identification and control of pandemics – require such a jersey of expertise from very different fields, in particular engineering, policy, economy and data analysis. This awareness guided him, a decade ago, in the creation of the Pioneer Institute of MIT for data, systems and society (IDSS), aimed at promoting a more deeply integrated and durable collaborations than the usual temporary and ad hoc associations that occur for such work.

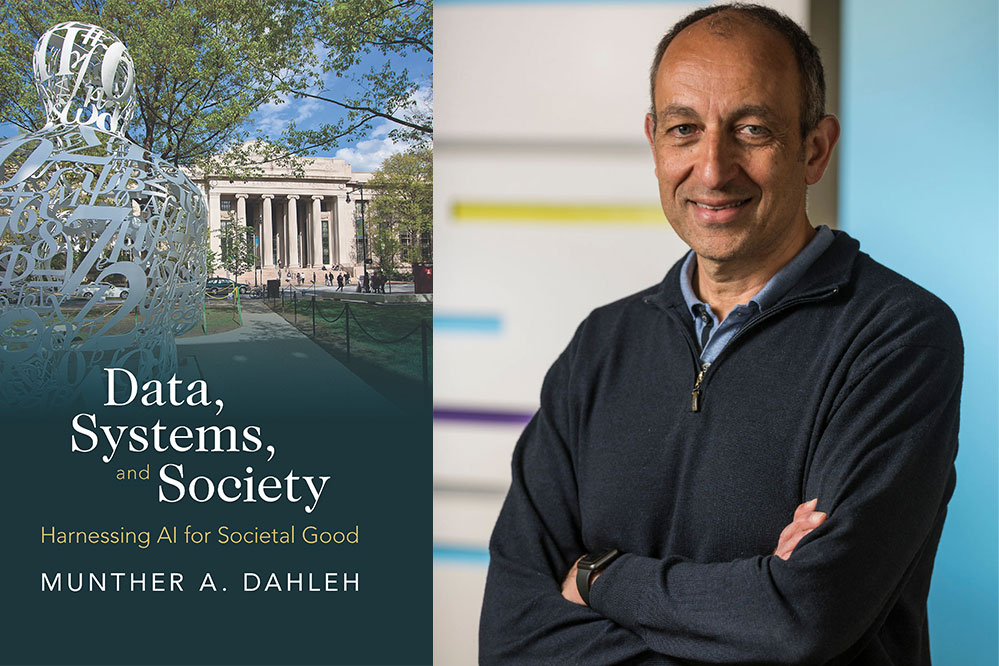

Dahleh has now written a book detailing the landscape analysis process of existing disciplinary divisions and designing a means of creating a structure aimed at breaking some of these obstacles in a lasting and significant way, in order to provoke this new institute. The book, “Data, systems and company: AI Exploitation for the good of the company“, Was published in March by Cambridge University Press.

The book, says Dahleh, is his attempt to “describe our thought which led us to the vision of the institute. What was the engine vision of this one? ” It is aimed at a number of different audiences, he says, but in particular: “I target students who come to do research that they want to meet societal challenges of different types, but using AI and data science. How should they think of these problems? “

A key concept that guided the structure of the institute is something he calls “the triangle”. This refers to the interaction of three components: physical systems, people interacting with these physical systems, then regulations and policy concerning these systems. Each of these effects affects and is affected by others in various ways, he explains. “You get a complex interaction between these three components, then there is data on all these parts. The data is a bit like a circle that is in the middle of this triangle and connects all these parts, ”he says.

When solving a large complex problem, he suggests, it is useful to think in terms of this triangle. “If you attack a societal problem, it is very important to understand the impact of your solution on society, on people and the role of people in the success of your system,” he said. Often, he said, “solutions and technology have in fact marginalized certain groups of people and ignored them. The big message is therefore always to think about the interaction between these components when you think about how to solve problems. ”

As a specific example, he quotes the Pandemic COVID-19. It was a perfect example of a big societal problem, he says, and illustrates the three sides of the triangle: there is biology, which was little understood at the beginning and was subjected to intensive research efforts; There was the contagion effect, linked to social behavior and interactions between people; And there was decision -making by political leaders and institutions, in terms of closing schools and businesses or demanding masks, etc. “The complex problem we encountered was the interaction of all these components that occur in real time, when the data were not all available,” he said.

Take a decision, for example, to close schools or businesses, depending on the control of the propagation of the disease, has had immediate effects on the economy and social well-being and health and education, “so we had to weigh all these things in the formula,” he said. “The triangle came to life for us during the pandemic.” Consequently, the IDSS “have become a place of reception, partly because of all the different aspects of the problem that interested us”.

Examples of such interactions abound, he says. The platforms of social media and electronic commerce are another case of “systems built for people, and they have a regulatory aspect, and they integrate into the same story if you try to understand the disinformation or monitoring of disinformation.”

The book presents many examples of ethical problems in AI, stressing that they must be treated with great care. He cites autonomous cars as an example, where programming decisions in dangerous situations may appear ethical but lead to negative economic and humanitarian results. For example, while most Americans support the idea that a car should sacrifice its driver rather than killing an innocent person, they would not buy such a car. This reluctance reduces adoption rates and ultimately increases the victims.

In the book, he explains the difference, as he sees it, between the concept of “transdisciplinary” research compared to typical interdisciplinary or interdisciplinary research. “They all have different roles, and they have succeeded in different ways,” he says. The key is that most of these efforts tend to be transient, which can limit their societal impact. The fact is that even if people from different departments work together on projects, they do not have a structure of shared journals, conferences, common spaces and infrastructure, and a feeling of community. The creation of an academic entity in the form of an IDSS which explicitly crosses these borders in a fixed and sustainable way has been an attempt to resolve this lack. “It was mainly a question of creating a culture so that people reflect on all these components at the same time.”

He rushes to add that of course, such interactions are already performing at MIT, “but we did not have a place where not all students interact with all these principles at the same time.” In the doctoral program IDSS, for example, there are 12 basic courses required – half of them statistics and theory and calculation of optimization, and half of the social sciences and the human sciences.

Dahleh left the management of IDSS two years ago to return to teaching and continue his research. But while he was thinking about the work of this institute and his role in the creation of his entry, he realized that unlike his own academic research, in which each stage along the way is carefully documented in published articles, “I have not left a path” to document the creation of the Institute and the reflection behind. “No one knows what we thought, how we thought about it, how we built it.” Now, with this book, they do.

The book, he says, is “in a way the people who led people to the way it all met, with hindsight. I want people to read this and understand it from a historical perspective, how something like it happened, and I did my best to make it as understandable and simple as possible. ”