Photo graceful of the Washington State University.

It has become fashionable in recent years to observe that we live in an increasingly beige and gray world from which all colors are drained. Whether or not it is really the case, we all always have easy access to a range of colors that no one in the ancient world could have imagined, and not only through our screens. Look around you and your eye will soon fall on an object or another whose shade alone would have seemed incredibly exotic in the civilization of, let's say, ancient Egypt. My cup of coffee Offers a simple but lively example, with its blue-green, and perhaps yours too.

“Most ancient pigments came from natural resources – ocher, charcoal or lime, for example,” Writes Ben Seal at the Pittsburgh Carnegie Museums. “In some cases, the Egyptians were able to use Lapis Lazuli, a metamorphic rock that was found in Afghanistan, to represent the blue color.” But such a “prohibitive and completely impracticable” source, because Seal quotes Carnegie Museum of Natural History Egyptologist Lisa Haney describing her, motivated the ancient Egyptians to find “a process to emulate his intense ultramarine shade.

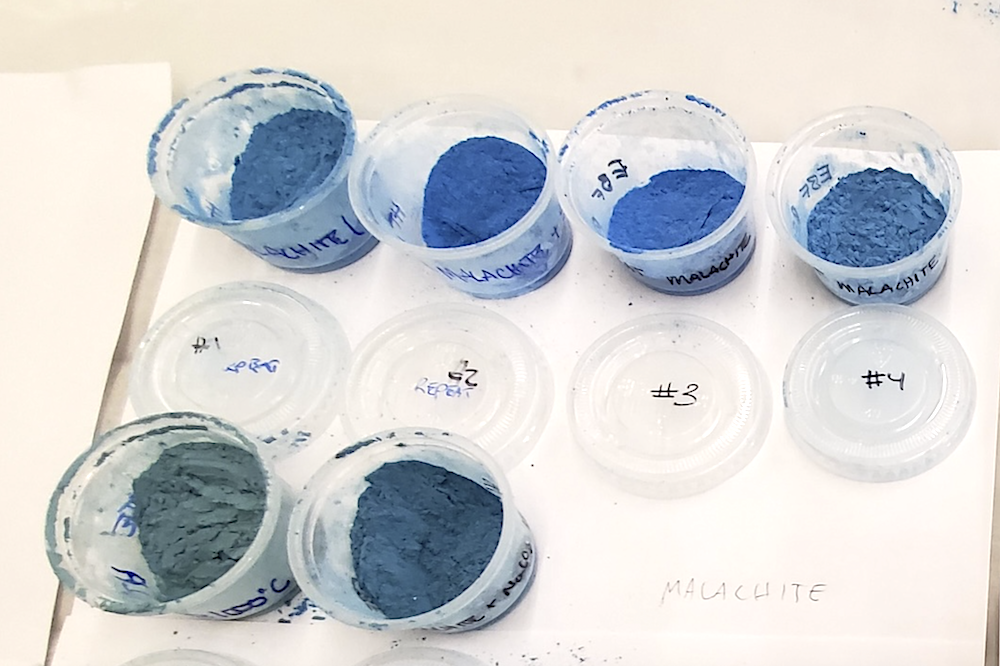

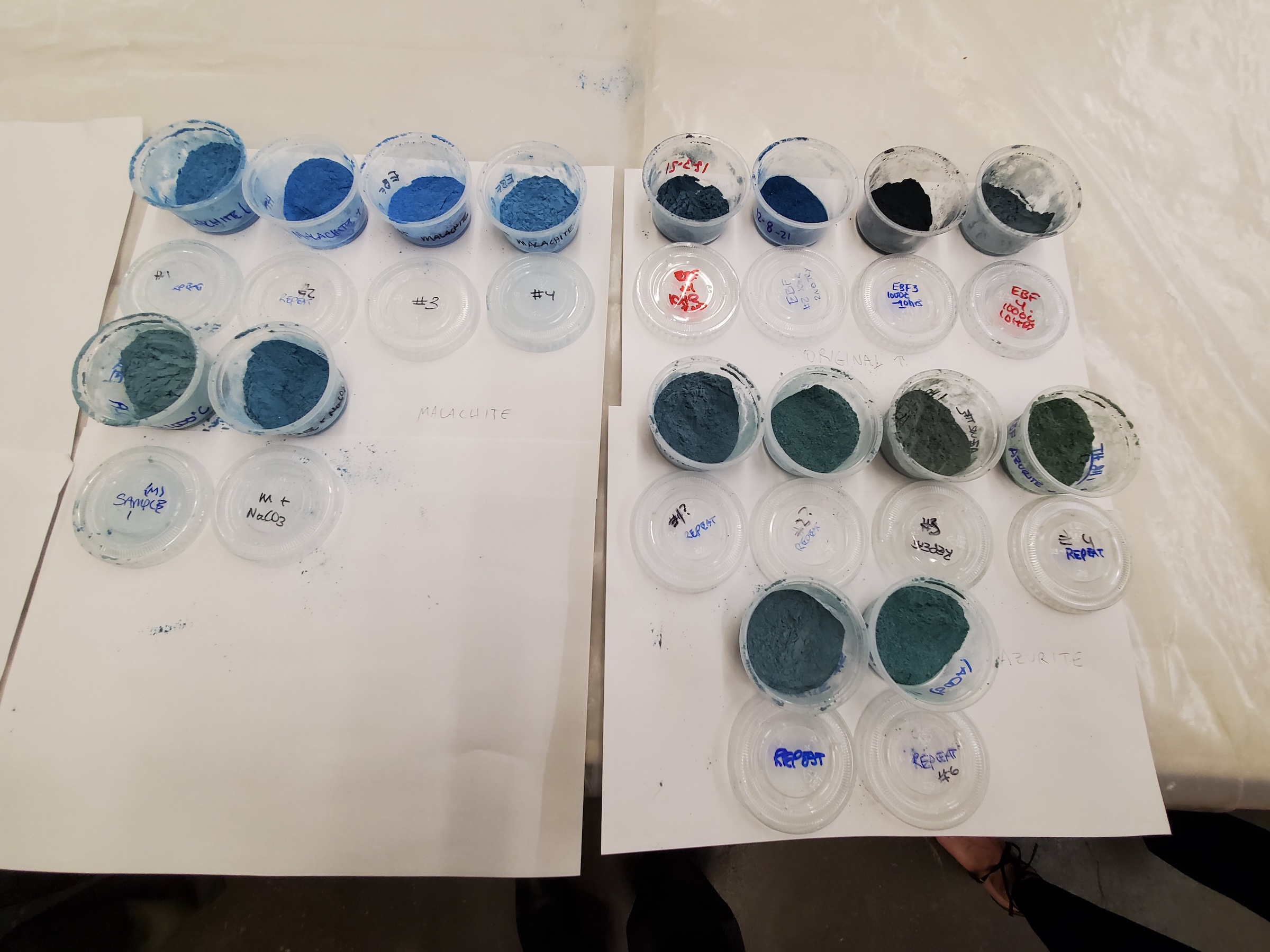

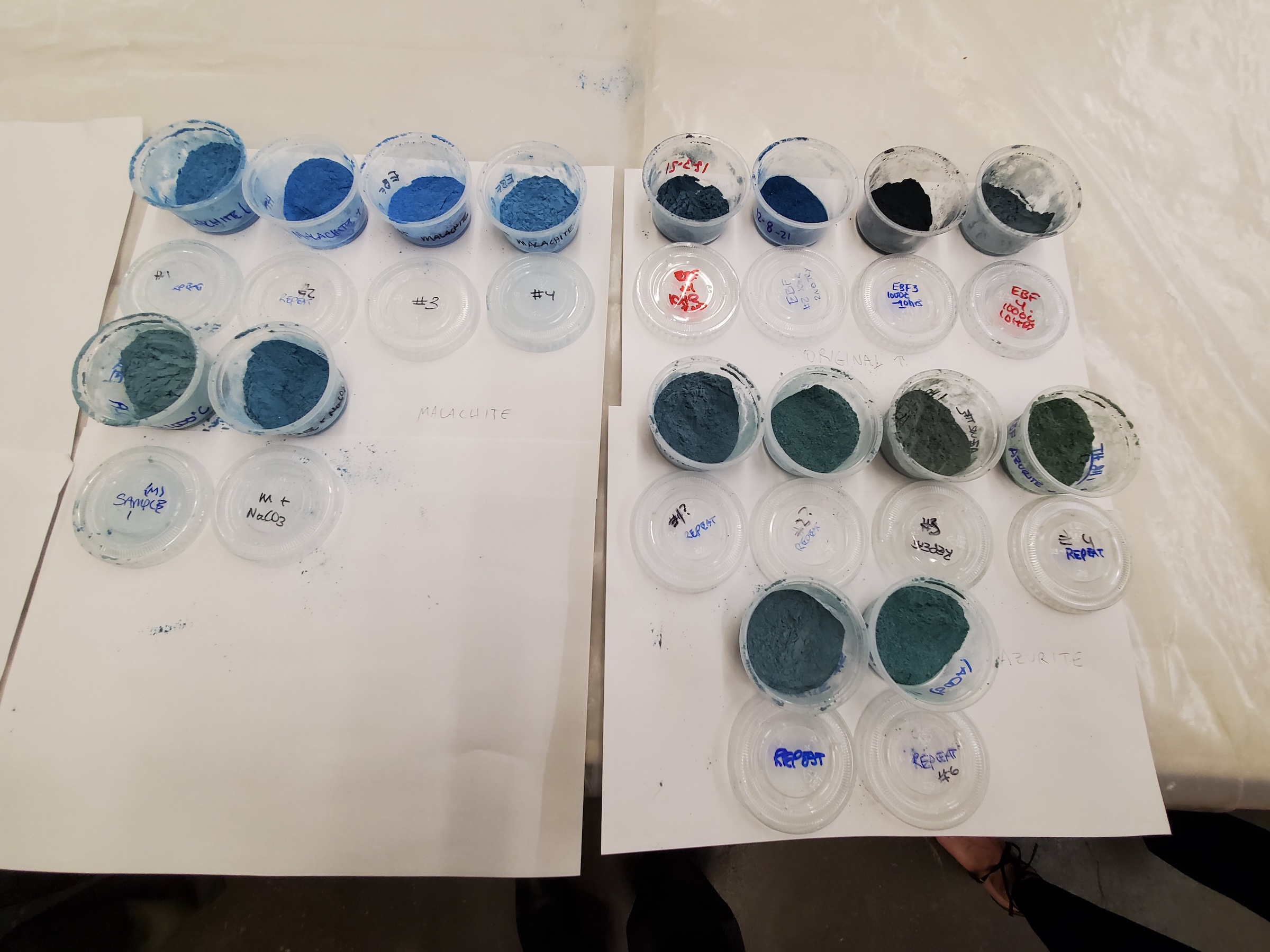

Last May, Haney and a team of other CMNH researchers, Washington State University and the Smithsonian Institution's Museum Conservation Institute Published an article On their work of recreation of what is called “Egyptian blue”, the first known synthetic pigment. Existing on artefacts and also used, it seems, in ancient Rome, and at least once in the Renaissance (no less a man of the Renaissance than Raphael) Its original recipe has since been lost in history. Using period materials such as “calcium carbonate that could have been drawn from limestone or shells; quartz sand; And a source of copper “heated to around 1000 degrees Celsius, writes Seal:” The researchers have prepared nearly two dozen powdered pigments in a superb range of blues. “

Photo graceful of the Washington State University.

The key was to reproduce the cuporivaite, “the mineral which gave the Egyptian blue such resonance”, and one of these experimental powders turned out to be 50% of cuporivate in volume. The resulting pigment, as Brian Boucher d'Artnet writesis more than historical interest, with potential modern uses “due to its optical, magnetic and biological properties. It emits light in the near infrared part of the electro-magnetic spectrum, which people cannot see. Here, in the 21st century, we can have all the blues we need, but as in the ancient world, the work of keeping a step ahead of the counterfeiters is never done.

via Hyperalgic

Related content:

Here are the Egyptian, Greek and ancient Roman sculptures in their original color

Why most ancient civilizations had no word for blue color

Based in Seoul, Colin MArshall Written and broadcastTS on cities, language and culture. His projects include the substack newsletter Books on cities And the book The stateless city: a walk through Los Angeles from the 21st century. Follow it on the social network formerly known as Twitter in @ColinmArshall.