The advancement of information and communication technologies (ICT) has considerably had an impact on society, transforming the way we live, work and learn. In this last aspect, ICT has become fundamental support, opening up new possibilities and opportunities. Thus, in recent decades, online education has experienced significant growth (Karademir Coşkun & Alper, 2019; Wallace-Spurgin, 2020). Educational platforms, online training courses and digital resources are presented as learning opportunities accessible worldwide. However, is online education really accessible to everyone, including disabled adults? And is the provision of this training sufficient for this group? Although ICTs offer important opportunities, access to online training is not always equitable, with challenges in particular for disabled adults.

According to the World Health Organization (2023), it is estimated that around 1.3 billion people worldwide have a form of disability, representing 16% of the world's population. In Europe, the European Union Council (2022) reports that 101 million adults live with disabilities, representing 27% of the adult population. They also note that the most affected age groups are those between 45 and 64, as well as those over 65. In addition, within the European Union, the prevalence of disabilities is higher in women, with 29.5%, against 24.4% among men (European Union Council, 2022).

We must keep in mind that people with disabilities meet a multitude of challenges. Compared to those who have not disabled, they experience higher unemployment rates, an increased risk of poverty or social exclusion, greater sensitivity to violence and abuse, lower academic performance and a rate of abandonment of higher schools (Council of the European Union, 2022). In this context, online education could help alleviate some of these problems, potentially improving the quality of life of disabled people and promoting their social integration. In addition, article 24.5 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPC ratification instrument, December 13, 2006, April 21, 2008) explicitly recognizes the right to education for disabled people:

States parties ensure that people with disabilities have general access to higher education, vocational training, adult education and lifelong learning without discrimination and on an equal level with others. To this end, the States Parties will ensure that reasonable adjustments are made for disabled people (article 24.5, p. 96)

In this regard, online training could offer several advantages compared to face -to -face training for people with disabilities. For example, its adaptability allows training to personalize according to the profile, the learning style of the individual and the specific needs (Aeiadand & Meziane, 2019). Online training also offers flexibility in terms of when the training is accessible, allowing learners to give their own pace and thus promote greater autonomy in learning. Another key characteristic of online education is its accessibility, both in terms of time and location, which allows learners to access the formation of any place (Herrera et al., 2015). In addition, some studies (for example, Biggs & Tang, 2011) have noted that for people with autism spectrum disorders (TSA), asynchronous participation in discussions can reduce stress by allowing them to respond to their own pace.

Given these advantages, there has recently been a considerable increase in online learning or virtual learning environments developed specifically for people with special educational needs (Ozdemir et al., 2019). These environments include a range of tools such as online learning platforms, collaborative learning environments, virtual classrooms, 3D simulators and virtual environments, as well as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR). These emerging technologies are explored for their potential to improve educational experience by offering immersive simulations and more engaging learning environments. For example, Contreras-Ortiz et al. (2023) Note that technologies such as VR, AR and Mobile applications are particularly implemented with autistic people, alongside other environments used.

These educational environments are versatile, allowing the development of a wide range of skills, including academic, social, emotional skills, communication, personal and cognitive autonomy, among others. For example, Howard and Gutworth (2020) Emphasize the potential of virtual reality (VR) to improve social and emotional skills in autistic individuals.

However, key questions remain: what components or elements should an learning environment include significant learning for disabled people? In addition, what skills should individuals interact effectively with online environments?

Search for Meyers and Bagnall (2015) and Downing (2014), which reflects the perceptions of autistic students, underlines the need for clear instructions and presentation of the equipment. They recommend minimizing the number of resources and links available. In accordance with these results, it is crucial to design simpler environments that have clear, specific, simple, literal and easy-to-follow instructions (Contreas-Ortiz et al., 2023).

Adams et al. (2019) has identified several obstacles and facilitators in the learning experience of autistic university students. Among the obstacles, notable problems include the overwhelming quantity of information on a page, the need for immediate answers to their questions, the difficulty in planning the calendar, excessive workloads and pressing deadlines. Conversely, facilitators include the possibility of taking a break and replaying videos, flexible planning, quick responses to requests, availability of evaluation sections and detailed calendar. The authors highlight the importance of the interaction and creation of collaborative learning communities. However, they warn that the nature and frequency of these interactions can either hinder or help autistic students, thus stressing the need to establish a functional virtual community (Garrison, 2017). Additional studies (Contreas-Ortiz et al., 2023) Highlight the essential characteristics of an effective online environment. These environments must be dynamic, incorporating a variety of resources and a robust learning support system, and must adapt to meet the needs and individual preferences (Brown, 2000). For people with TSA, it is crucial to include visual elements such as videos and images, use authentic images, provide specific instructions and use a natural voice in presentations. In addition, teaching strategies must integrate positive reinforcements, gradually increase the difficulty of activities and ensure in-depth supervision and monitoring throughout the teaching-learning process (Contreras-Ortiz et al., 2023). Acosta et al. (2020) Also provide recommendations to create accessible and inclusive online content. These directives align with the accessibility directives of creation tools (ATAG) 2.0 of the World Wide Web Consortium. They design online training programs for people of all ages with disabilities. In the end, any intervention or training must be adapted to the specific needs of its target population.

The key skills necessary for successful online learning include self-regulation, self-discipline, time management, organization and self-assessment. These skills, crucial for engagement with learning content, are highlighted in a Kauffman review (2015) and moreover supported by research by Serdyukov and Hill (2013). In addition, digital competence is essential for effective interaction with online platforms and resources, especially for disabled adults.

Despite a significant increase in the last decade of the number of publications on interventions and training in online environments, VR / AR, etc., in various population groups (for example, Dechsling et al., 2020; Mesa-Gresa et al., 2018; Lorenzo et al., 2018), and the positive results of the implementation of ICT in training processes (Contreras-Ortiz et al., 2023), a critical question remains: what do we really know about online training for disabled adults?

Several review studies have studied virtual and augmented reality (VR / AR) in educational interventions for autistic people. For example, studies by Mesa-Gresa et al. (2018) and Lorenzo et al. (2018) mainly focused on autistic children. Expanding this demographic scope, the search for Dechsling et al. (2022) examined literature on autism interventions using VR / AR in different age groups. Their analysis of 49 articles revealed that one study (Amaral et al., 2018) Included participants over 31, without studies involving individuals over 40 years of age. Likewise, Contreras-Ortiz et al. (2023) examined online learning ecosystems for people with ASD, observing a significant gap in adult research. An online learning ecosystem incorporates all the essential components necessary to implement an online learning system, as discussed in studies by Ezzahraa et al. (2020) and Luna-Encalada et al. (2021).

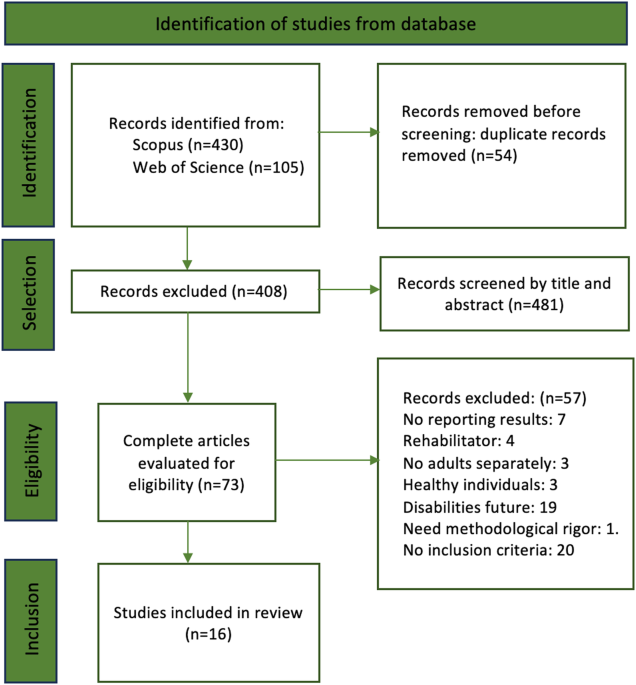

To our knowledge, no study of previous journals specifically aimed to analyze online training for disabled adults. Given the rapid development of online learning and the notable lack of information on this demography, there is a clear justification to carry out an examination to map and systematically assess existing research in this area.

The purpose of this review is to provide a complete summary of studies that have used online training formats for disabled adults. This implies evaluating the literature, including the methodologies used, the variables analyzed and the characteristics of the training program. In addition, this review aims to identify research shortcomings in the existing literature.