The history of medicine is, for the most part, a story of doubtful remedies. Some were even worse than doubtful: for example, the ingestion of antimonythat we now know how to be a highly toxic metal. Although it cannot occupy an exalted place (or, for students in chemistry, particularly memorable) on the periodic table today, antimony has a fairly long cultural history. Its first known use took place in ancient Egypt when Stibnite, one of its mineral forms, was crushed in the Kohl cosmetics of the surprisingly dark eyeliner type, which was supposed to remove the evil spirits.

Ancient Greek civilization has recognized antimony less for its effects on the world of minds than on the human world. The Greeks knew very well that the things were toxic, but also continued to return there as a potential form of medicine.

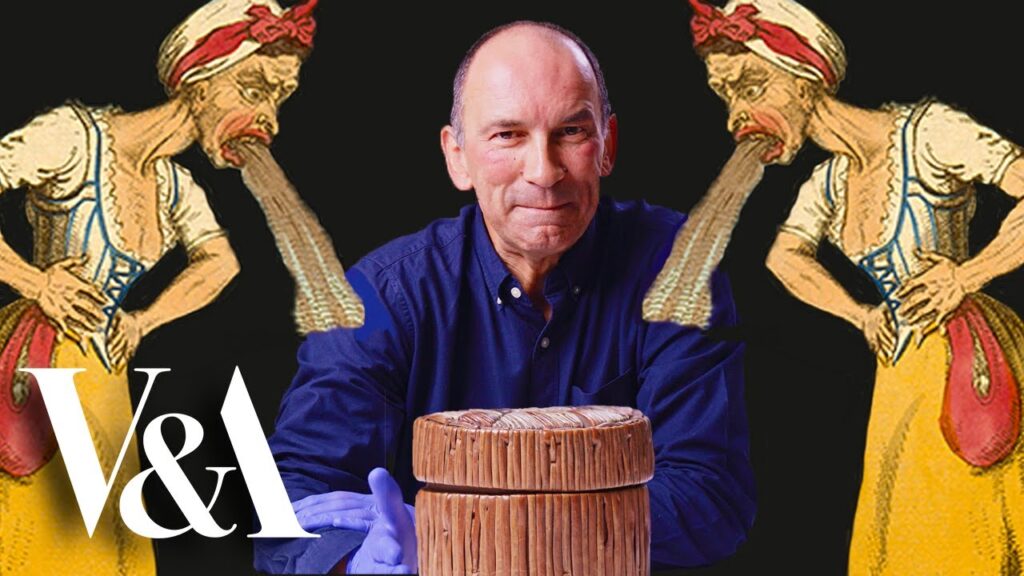

Ancient Rome has made its own practical use of antimony, especially in metallurgy, but has also kept certain survey lines on its healing properties. As a substance, it was well placed to capture the imagination more intensely in the medieval era of alchemy. At the end of the 17th century, people drank wine from cups of antimony, as not overwhelmed The video of the Victoria and Albert Museum above.

“The goal is to try to make you vomit and have diarrhea and sweat a lot,” explains Angus Patterson, the senior curator of metal V&A. In theory, this rebalances “moods” whose medieval medicine conceives the body as composed. Fantasy cups like that of video, which formerly belonged to a Lord, were not the only antimony objects used for this purpose: metal was also forged by supposedly “perpetual pills”, intended to be swallowed, recovered from excrement, then swallowed again if necessary – for several generations, in certain cases, as family hyiroloma. “I am not sure I want to swallow a pill that had crossed my grandfather,” adds Patterson, “but the needs owed when you have stomach pain in 1750.”

via Infinite time

Related content:

The color that may have killed Napoleon: Scheele green

1000 -year illustrated guide on the medicinal use of plants now scanned and put online

The healing of Sir Isaac Newton for the plague: Tapon Powder Lozenges (1669)

Based in Seoul, Colin MArshall Written and broadcastTS on cities, language and culture. His projects include the substack newsletter Books on cities And the book The stateless city: a walk through Los Angeles from the 21st century. Follow it on the social network formerly known as Twitter in @ColinmArshall.